40 years of Bomberman: Bomberman at the arcade

Bomberman didn't start in the arcade, but the series made its way there more than a couple of times over the years.

July marks 40 years of Hudson Soft’s (and Konami’s) Bomberman franchise. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Bomberman games, the versatility of its protagonist, and the legacy of both. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

Unlike a not insignificant number of video game franchises born in the 1980s, Bomberman didn’t get its start in the arcade. It was released on Japanese computers — a couple of which were also available in Europe — in 1983, and then the more famous iteration of Bomberman came out on the Famicom in 1985 and the NES in ‘89. It’s been primarily a console, handheld, and sometimes computer franchise since, but Bomberman did have a short run in the arcades for a time there, as well as a fairly recent return of sorts under Konami’s banner.

Hudson Soft, the creator of Bomberman, didn’t bother developing these arcade titles themselves. Their expertise was in the living room, so that’s where they stayed, and instead the arcade-focused Irem obtained a license from Hudson to make a game there. They’d end up making three, sort of: the first and a sequel, and then a third game later on developed by former Irem employees in a different studio.

Irem wasn’t exclusively an arcade developer by any means, but they got their start making games for arcades in 1978, and kept at it through 1994 before switching over to at-home platforms for good. Irem loved a shoot ‘em up and an action game, with titles like Moon Patrol, X-Multiply, Image Fight, Legend of Hero Tonma, Ninja Spirit, In the Hunt, and, of course, the R-Type franchise fitting that bill for arcades in Japan and sometimes internationally as well, and with quite a few of those receiving at-home ports as well. While they would occasionally port one of their arcade games themselves, sometimes it was left to another party to do so… like when Hudson Soft ported R-Type to the PC Engine and Turbografx-16, a version that was, at one time, the best way to play that classic STG at home, given it was more powerful than what the Sega Master System or NES could spit out.

In that sense, Irem taking Hudson’s budding flagship franchise and putting it in arcades feels like returning a favor, as well as two companies utilizing their respective expertise to the benefit of both parties: Hudson lacked robust arcade experience, had their own console to worry about as well as development for others, and were known for their quality port work, while Irem’s console development, at the time, was often step two after an arcade game had already been created.

The only curious decision in this partnership was that, in North America, Irem decided against using the Bomberman name for the game, and instead borrowed that of a Game Boy game that was very much Bomberman, but just didn’t look like it in name or cover art. Atomic Punk released in Japan in 1990 as Bomber Boy and 1991 in North America as Atomic Punk, and the cover of the latter featured a robot boy with a rainbow mohawk wielding a bomb, threatening foes with it. Atomic Punk was a successful Game Boy game, sure, but this kind of just goes to show that Hudson’s bit of meandering at the start of Bomberman’s life — Bomberman, Bomber King, RoboWarrior, Bomber Boy, Atomic Punk — meant it wasn’t plainly obvious that a game in the Bomberman series should have the word “Bomberman” in it. It probably didn’t help that European releases were called Eric and the Floaters or Dynablaster to make sure they didn’t appear to be promoting bombings, either.

Another curiosity, though, this one has nothing to do with Hudson, is that the Bomberman and Atomic Punk arcade games were different from one another. The Japanese version included a four-player Battle Mode where human competitors could take each other on in what was becoming the series’ traditional multiplayer, and it’s also the first Bomberman game in which you could play the multiplayer against computer bots instead of requiring other people to compete against. (That the story mode includes enemies who can drop bombs just like you probably made that decision a much easier one to implement.) Atomic Punk didn’t include this Battle Mode, but what it does have on the Japanese version is the jump from two player story mode co-op to four. The game’s story is based around the idea that King Bomber betrayed his partner in arena-based explosion sports, Bomberman, to give world domination a go. So Bomberman teams up with his brother and new partner — I kid you not — Bomberman 2 to take on King Bomber and save the world. The story doesn’t say so in North America or Europe, but it’s easy enough to assume that Bomberman just has some other brothers he’s partnering with, and they’re named Bomberman 3 and Bomberman 4. It becomes pretty easy to understand why Hudson just started naming them all after colors as more and more Bombermen were introduced.

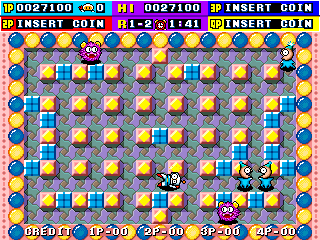

If the way the game plays solo is any indication, the four-player mode must be absolute chaos, but the good kind. Every stage, your powers are reset, which means you need to find new upgrades for carrying more bombs, causing bigger explosions, running faster, using remotes to detonate, and so on each time you’re in a new level. But it works, because the explodable soft blocks have upgrades in them more often than not, meaning there are plenty of upgrades to go rushing after out of the gate instead of the typical slow build of Bomberman. Combined with the single-screen real estate and the highly aggressive enemies, you’ve got a much faster-paced game that fits the arcade much more than simply replicating the existing Bomberman experience would have. Atomic Punk is Bomberman, yes, but it’s Bomberman made for the arcade in more ways than one. See? Irem using their expertise wasn’t just a convenient thing to say: that’s a company that knew what made for a successful and enjoyable arcade experience vs. an at-home one.

As is the norm for Bomberman games, you score more points with combos of exploded foes, which you’ll need to make more and more dangerous explosions to be able to pull off. There’s also a matchstick item you can pick up in Atomic Punk, hidden in the soft blocks like other items, that’s worth 5,000 if you pick it up. Considering the basic foes are worth all of 100 points when you defeat them, the matchstick is a huge get, which is also why that score shows up in a much larger and attention-grabbing font. You can also string together kills and pick-ups to score far more than 5,000 on a single combo, too, so those points can start to rack up in a hurry if you know what you’re doing… and can avoid being blown up by bombs, yours or otherwise, while you do it.

Speed and difficulty. There’s loads of both in Atomic Punk, and the chaos of four players on screen at once all rushing for power ups while trying not to blow up their pals adds to the feeling of both. Arcade 1Up needs to release this thing in a mini cabinet, or Hamster needs to get it on Arcade Archives, because I simply must experience Atomic Punk in its most chaotic form instead of just the single-player — which is plenty chaotic on its own thanks to the enemies that hunt you down and the game’s general enhanced pacing and speed.

Irem would make a sequel to Atomic Punk the following year, which was known as Bomberman World Arcade, but New Atomic Punk: Global Quest in North America. (The European version followed North America’s naming convention, only with “Dynablaster” subbed in for Atomic Punk.) As Steven Barbato pointed out at Hardcore Gaming 101 in that site’s review of the game, this would be both the final Atomic Punk entry as well as the final Dynablaster: Bomberman, from this point forward, would have its games under the Bomberman banner. As also pointed out, this one is a bit of a step backwards in some ways from the wonderfully balanced chaotic energy of the original Bomberman arcade entry.

Every version of the game now has four-player co-op, which is a positive, and it adds some new power-ups while adjusting old ones, but overall it turned the Arcade Difficulty dial just a little too far, and made for a less enjoyable game in the process. There’s an inherent difficulty to Bomberman that patience can help overcome, but Atomic Punk’s frenetic pacing made it so patience was difficult to display, meaning you could self-detonate more often than you would at home. It was fun, though, and avoiding such instances provided a rush. With the speed turned up a bit more in the sequel, though, those moments are more difficult to come by.

It’s still fun, because it’s still Bomberman. It’s just less fun because the balance that worked so wonderfully the year before was upset, and the other changes didn’t do enough to offset that. I will say, though, that King Bomber going after the United Nations as a way to kick off a sequel is pretty funny, in the sense that there didn’t need to be any consistency as to where Bomberman games were set at all at this point.

The last of the Irem “trilogy” came by way of developer Produce! and was published by Hudson Soft. Produce! was another Japanese developer, founded by former Irem employees in 1990. Given Atomic Punk wasn’t released until 1991, it’s not as if it’s all the same employees who worked on these projects, but it noteworthy to consider that Irem employees, former and actual, were responsible for so much Bomberman in the first decade-plus of the franchise. Irem itself produced the two arcade titles in ‘91 and ‘92, and Produce! made not just the Neo Geo MVS title Neo Bomberman, but were also the developers on three of the five Super Bomberman games on the Super Famicom/SNES: the original, its sequel, and the Japan-exclusive 4. (Hudson and Produce! had a solid relationship that extended beyond Bomberman, as well: Produce! developed Super Adventure Island on the SNES, the Hudson-published Aldynes: The Mission Code for Rage Crisis for the SuperGrafx, Hudson’s Dual Heroes on the Nintendo 64, and a fighting game entry in the role-playing franchise Tengai Makyō for the PC-FX. Most of the rest of their work was published by Enix or Namco.)

Graphically, Neo Bomberman is kind of on its own, which makes sense given that it wasn’t even Produce!’s artists putting it together, but those of ADS. And the audio came by way of Now Production’s sound team — Neo Bomberman is kind of a mishmash of multiple Hudson partners. Stylistically, it looks very much like pre-rendered sprites placed into a 32-bit 2D world, whereas another 32-bit Bomberman, Saturn Bomberman, looks like an extension of the more cartoon-y Turbografx-16/PC Engine style, only with more detail and improved animations.

Like with Atomic Punk and its sequel, Neo Bomberman has never received a home release. Not even as part of the Neo Geo-specific portion of Hamster’s Arcade Archives series! In what is not at all a shocker given the developer, gameplay is fairly reminiscent of the Super Bomberman games. It lacks the speed of Atomic Punk, and stuck to two-player co-op for the story mode, but it’s still a reliably entertaining Bomberman title, and given the relative lack of arcade options for the series by May of 1997, that’s not a bad thing even if you could hope for more.

It’s a little odd that Neo Bomberman never received a home conversion, but maybe it’s just a matter of timing. Hudson wasn’t exactly struggling to put original Bomberman games on consoles at this point — the Sega Saturn, Nintendo 64, and Playstation all had multiple Bomberman games exclusive to them, and the Game Boy and Game Boy Color were receiving plenty of attention on that front, too. The Neo Geo AES (the at-home model of the system) and Neo Geo CD would also be discontinued in December of 1997, a little over half-a-year after Neo Bomberman’s release, so maybe Hudson didn’t feel like it was worth the effort to make the conversion to those platforms at the end of their officially backed lives.

It would be the final Bomberman game produced in the arcades by way of Hudson Soft, whether through their licensing out the character to Irem or publishing themselves. Hudson would be purchased by Konami in the following decade and then closed and folded completely into the behemoth in the one after that. Konami would eventually get to making a Bomberman game for arcades… sort of. In the form of Bombergirl, which is a Bomberman-style game with anime-style moe girls all competing to blow up the clothes of the other anime girls, who are styled in the color patterns (and with accessories in the shape of) various Bomberman and other Konami characters.

Bombergirl started out in arcades, and became a free-to-play gacha game on PC after that. It’s only available on Windows 10, and while it’s Japan-exclusive, it can be accessed through Konami’s e-Amusement portal.

I tease the decision to make a Bomberman in the vein of their Horny Gradius game, Otomedius, sure, but it also looks pretty fun to play, and like a true expansion of the Bomberman formula. There are four different character classes that play in different ways: one can plant more bombs faster, another can attack from a distance, and so on. Characters have special skills, too, which in addition to the various classes makes them more than just a choice for which one you think looks the best, cutest, etc.

The beta originally worked like the arcade game, with you having to buy tickets to play, but it’s since become free-to-play. If you’ve got a Windows 10 system and don’t mind a whole bunch (but not all) of text in Japanese, you can give it a whirl, but it would be nice to just get an official international release now that it’s been out of beta for nearly two years. Seems unlikely at this point, however, given how quietly Konami is celebrating Bomberman’s 40th with just the one announced title.

For my money, Atomic Punk is the best of this bunch, as it had that great balance of speed and difficulty that made for what truly felt like a different experience than what you could just play at home. Basically, out of the gate, Irem showed why a Bomberman in the arcades made sense even though there (already) wasn’t a shortage of Bomberman to play at home; no one quite captured that same energy afterward, but at least we got Atomic Punk in the first place. Now, if only Konami would partner with Hamster to release that via Arcade Archives like they have so many of their in-house developed games, and then everyone could see that for themselves without needing to know how to operate MAME.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.