Retro spotlight: Xevious

One of the most influential and impactful video games ever, to the point that even developers who didn't make shooting games credit it for inspiring them.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Outside of Japan, Xevious wasn’t considered anything special. It’s not that it failed in North America, but its success in the arcades could be described as modest. In Japan, however, Xevious was a sensation, a clear next-step for the shooting game genre that would serve as the new template for vertical shooters in the same way that Space Invaders had, just a few years prior, influenced the entire direction of the industry and genre. Namco had made shooters before, and highly successful ones — Galaxian built off of the Space Invaders model, while Galaga ended up doing such a tremendous job of things there that it’s easy to forget that it was a sequel and not the start of something else entirely. But Xevious actually was something else entirely.

Like Space Invaders — as the original home license game — had been a killer app for the Atari 2600, Xevious played this role for Nintendo’s Famicom: it sold 1.26 million copies in Japan alone in 1984, helping to push the popularity of the system itself in its second year, in what was still a pre-Super Mario Bros. world. It was ported to the Apple II, the Atari 7800, the Atari ST, ended up on the Famicom Disk System, the Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, X68000, the FM-7, the Sharp X1, the PC-88 and PC-98, and the ZX Spectrum. An unlicensed Sega Master System version released in South Korea in 1990. It has been continually re-released in more modern times, with it being selected as one of the NES titles to get the Classics treatment on the Game Boy Advance, with a re-release packaged with multiple remakes on the Playstation, through multiple of Nintendo’s Virtual Consoles, as an Xbox 360 game available on that system’s digital marketplace, on mobile phones, as a remake presented in 3D on the Nintendo 3DS, across multiple platforms through Hamster’s Arcade Archives, and, of course, through various Namco Museum collections across the past couple of decades. You have to look pretty hard to find an era of video games where Xevious wasn’t available.

There’s a certain simplicity to Xevious these days, considering it’s over 40 years old at this point, but the only reason it seems simplistic is because everything that it did was absorbed into game development and game design at large, allowing its ideas to grow and expand into what they’ve become today. Galaga’s whole structure was much more mobile than that of Space Invaders given it had a few years to iterate, but it was still a fixed-shooter, i.e. one where you maneuver along a single axis. There was no scrolling: enemies arrived, lined up in formation, and then descended toward the bottom of the screen. Every level looked the same, as they were all just a black background dotted with twinkling stars, and the change from stage to stage came from the enemy formation and complexity.

Even when the genre made some steps forward — Kemco’s Red Clash, for instance, was a continuous scrolling shooter released in arcades in 1981, and with free movement for your ship, but it still had the same kind of backgrounds as Galaga. It didn’t all come together into a clear, agreed-upon direction before Xevious. Everything would change beginning in December of 1982, when Xevious was out in arcades on its test run before its official release at the start of the next year.

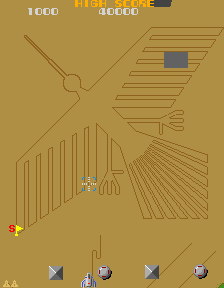

Xevious had continuous scrolling. You were able to freely move your ship on multiple axes, rather than in a fixed state. The starry black backgrounds were removed for detailed and differentiated environments: there are loads of trees, there are rivers, there are roads, buildings, and, famously, there are Nazca lines. There are not just enemies in the air with you, but also enemies on the ground, and you need to fire a different weapon to successfully defeat each type. Those ground enemies, too, followed the pattern of the earth they tread upon, which was something you could take note of as you strategized and prioritized: you weren’t going to start seeing little sci-fi tanks driving over water or on top of trees, you know, whereas in a space setting, with no structures in place, enemies could be anywhere at any time. There’s a reason that Play Meter’s Roger C. Sharpe wrote in 1985 that “dimensionalized, overhead perspective of modern, detailed graphics was launched with Xevious.” Namco’s shoot ‘em up wasn’t just different visually, but it engaged with this new form of dimensionality in a way that stuck, by differentiating between sky and ground, by adding more than just a layer of detail but a layer itself to games. (This specific design is also part of why it was an obvious candidate for the 3DS’ stereoscopic 3D capabilities; that’s a beautiful, but also highly practical, version of the game right there.) Games were bigger in every sense post-Xevious.

Xevious was one of the earliest games to include boss fights (nailing down the definite first is somewhat difficult for this sort of thing), which is one of those things that is so ingrained in games, especially shooters and action games of various stripes, that you kind of forget it had to even have an origin point. This is a recurring fight against the Andor Genesis, a massive flying station that you must defeat using the weapon meant for ground forces — it’s flying, but it’s below your ship, the Solvalou, with a weak spot protected by its outer bulk, and therefore you’ve got to bomb it instead of firing directly in front of you at it. Not only is this an early instance of a boss to defeat in a game, but there’s already a layer of scoring strategy to the proceedings: you can go right for the core at the center of the Andor Genesis and quickly defeat it that way, or you can pick off its various destructible parts on the outside of the ship to increase your score. It’s the riskier play, yes, but on the other hand: points. And since this is an arcade game, and points are how you earn extends, they’re useful whether you’re trying to show off on a leaderboard or just live long enough to see the game loop back to the beginning.

STG had not yet reached the point they would by the time of Capcom’s 1942 (released in 1984), with end-of-level boss fights. Instead, in Xevious, you either destroy the Andor Genesis or you run out of time to do so and it flies away to come back at you later. While there’s a change in the sound when the ship is about to arrive, that’s the only indication you get that something different is happening: there’s no literal flashing “Warning!!” like there would be in Darius down the road, no stop to what else is happening around you. Xevious pushes forward whether you’re in a boss battle or not, and when enough time has passed or you’ve managed to down the Andor Genesis, it pushes on still, now just without that boss.

On top of everything you can see, Xevious features invisible enemies, but also a way to detect them. While you fire your blaster directly in front of your ship without needing to aim, your bombs have a reticule that’s a little ways in front of your ship, to show where the bomb will land when gravity has done its job. This reticule will flash red when you’re hovered over a target… whether that target is visible or not. Which means that, on top of the visible enemies in the sky and on the ground, you need to keep an eye on the actual reticule and what color it is, to determine if there’s a hidden foe waiting to strike on the ground. Those shots that come out of seemingly nowhere? Those have an origin point, and it’s one you can only see if you put the reticule over it.

This is not the end of Xevious’ strategy, either. The game also features a notable rank system. For those who have forgotten to keep their STG glossary on hand, rank is, in this context, not where your score ranks on a leaderboard, but instead a rating plopped into an in-game calculation that determines how difficult (or not) your playthrough is going to be. This rating can change based on how you play, as in, how often you’re dying, how many enemies you’re killing, how many enemies you’re not killing, the number of shots you fire, how many bombs you’re keeping in reserve, how long it’s taking you to complete a stage, and so on.

Xevious’ rank system was not the first, but the specific form it took did end up as the template for countless other STG, and is the one people are most familiar with. The longer you stay alive and the more points you score, the more aggressive the Solvalou’s enemies become. They feel more erratic as they begin to move faster, and the game recognizes when you’ve had considerable success against specific enemy types, too: it’ll actually stop spawning those foes, and introduce more of the kinds you haven’t clearly mastered into the playing field, instead. You can reduce your rank in two ways: by destroying red towers on the ground, or by dying. You don’t want to do the latter, really, but it’ll happen sometimes just as a matter of course, and when it does, you can at least take solace in everything slowing down once more. While rank is traditionally a hidden system and calculation made again and again on the fly as you play, you’re able to choose to view it in the Nintendo DS release of Xevious, found on that system’s Namco Museum. That’ll give you a sense of exactly what feeds into the game becoming more or less difficult for you, as it’s happening.

Rank is at the heart of so many games, but Battle Garegga is probably the one for which it became the central mechanic to build around: that absolute masterpiece, like so many other games, exists because of the foundation that Xevious built. Xevious’ influence is even more obviously noticeable for the kinds of games that sprung up in its wake, like Konami’s TwinBee — a cute ‘em up with ground and air attacks and enemies that wowed with its own break from the geographic background norms of the day — or Terra Cresta, which, like Moon Cresta’s relation to Galaxian before it, took the formula behind Xevious, and then tweaked it just enough to make something completely new out of it. Like with Battle Garegga being the maximalist example of building around rank in an STG, Taito’s RayForce, aka Layer Section aka Galactic Attack, is the extreme result of pushing Xevious’ ground targeting to its logical conclusion. Making everything happen fast, making it happen incessantly, and building the only way to reliably earn any extends around a scoring multiplier that requires mastery of chained ground attacks.

Under most circumstances, the creator of a game — in this case Masanobu Endō — saying this about their creation would be grounds for all kinds of red flags and warning alarms to go off because good lord, the ego you require to even formulate the thought:

In the history of music, it’s said that the Beatles widened the scope of rock, and the Rolling Stones then took it further and deeper; in the history of video games, I think that Space Invaders and Galaga widened the scope of games, and Xevious took the baton and went further with it.

But the thing is, it’s an apt comparison, so even though Endō said this all the way back in 1985, you simply have to hand it to the man’s vision. Space Invaders revealed the appetite of the world for the new kind of video game it was. Xevious showed up a few years later, with a level of depth and innovation unseen in the genre to that point, and everything changed once again. In many cases, permanently so.

Xevious’ influence on shoot ‘em ups is the kind of thing you can’t unsee once you’re aware of it, to the point that Treasure’s founder, Masato Magaewa, explained in a 2001 interview that Xevious “formalized what we consider an ‘STG’ game to be,” and that the “fundamentals of STG are still dodging and shooting” nearly two decades after Xevious. He’d go on to say that:

After Xevious, STG developers tried to add items, power-ups, and all manner of gimmicks and contrivances to their new games. Some went the route of making STG games more flashy and outrageous, filling the screen with intricate danmaku patterns that were fun to dodge, or having awesome bombs and explosions, or an interesting backstory and gameworld. But for vertical STGs, even by Xevious we see many gameplay elements perfected. I would say the same thing for Gradius, also, as a horizontal STG.

There have been some absolutely incredible shooting games created since Xevious yes, but Magaewa is correct in that these basic fundamentals, this formalization of what a vertical STG even was, were pretty much solved by Xevious. Like everything briefly played off of Space Invaders, everything would soon be a reaction of some kind to Xevious in some way or another: Battle Garegga, TwinBee, RayForce, 194X, Raiden, Rez, all of it. For as different as Treasure’s Radiant Silvergun and Ikaruga are, they were still, by purposely eschewing the tradition of Xevious and subverting audience expectations of shoot ‘em ups in general, playing off of Xevious just as much as a game that strictly adheres to its design decades later in the process.

Xevious even, in a way, inspired the later works of Endō: seeing that Xevious was a game that could be completed on a single credit by an experienced player, and then played essentially forever if they were skilled enough, he set about making The Tower of Druaga, which would not only feature an immense increase in difficulty and learning curve, but have an actual ending, too — the first arcade game to feature such a hard stopping point, in fact. Players would have a reason to walk away from the machine, but they’d also have to put in a ton of effort to get to that point, too. And effort isn’t free in an arcade.

The love for and inspiration from Xevious was significant for non-shoot ‘em up developers, as well. The first thing Nintendo’s Shigeru Miyamoto mentioned in a conversation with Xevious’ creator Endō was his love for the game. Fukio “MTJ” Mitsuji, who would create the Bubble Bobble series for Taito, credited Xevious with making him realize what video games were even capable of. “The first time I saw it, it was the beautiful graphics that blew me away. Then when I actually played it, I felt a depth that I had not experienced before in video games—the story, the characters, the movements that had the quality of animation—all of that had a huge impact on driving me into video game development, I think.” And his drive to do well at Taito had a lot to do with trying to make that company as capable of producing the kind of quality that Namco did, quality that had resulted in titles like Xevious. In 2011, Hideo Kojima tweeted out that Xevious was one of the four games that has influenced him the most in his career, alongside Super Mario Bros., the Portopia Serial Murder Case, and cinematic platformer Another World. Xevious not only succeeded just from straight gameplay, but an entire world and story was built up around it — a real rarity for the day, one Endō cites as moving games closer to the worlds of anime and movies in terms of design — and it tied into its environments and the gameplay. It’s no wonder Kojima would think back fondly on its influence on him.

Xevious has certainly aged in some ways that make it a little tough for modern players to see the appeal of it — there’s just the one song going, for instance, and it’s a short one, and it is, as already said, a bit simplistic at this point. It was stunning both graphically and in its visual design in 1983 — Xevious was even already utilizing pre-rendered graphics at this early juncture — but it’s over 40 years later, so it looks less so these days. The gameplay loop still works, however, and should certainly seem familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of STGs made in the years after Xevious. It’s just understandable, for instance, that Namco took the opportunity on the Playstation to create an arranged Xevious more in line with modern expectations, as well as a full-on 3D remake, or that the most stunning edition of the game out there is the 3DS remake with its stereoscopic 3D that truly makes the world below the Solvalou pop, both literally and figuratively. We already know the foundational design holds up in the shooters it inspired, so why not give the original a fresh coat of paint when you’ve got the chance?

It’s still wildly playable even without said paint, despite its relative simplicity, so don’t take any of this as a slight against Xevious in the year 2024. It’s more just that the emphasis on Xevious, at this point, should be on what it stands for, what it succeeded at, what it produced, more so than how it still plays at this point. Namco simply wanted to steal some of Konami’s thunder in the arcades that had come from the horizontal shooter Scramble. They wanted to follow a market trend, in order to create a profitable game. They succeeded on both fronts, and then some, forever changing an entire genre and the industry as we know it in the process.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Thanks for this. I like SHMUPs, but I'm not familiar with their history. This is clearly an OG title of the genre.